Marketing

As the nineteenth century drew to an end, mainstream agricultural advertising was rife with images of full-bodied women and bountiful crops. Symbolic of abundance and prosperity, these icons stand in contrast to William S. Teator’s pamphlets.

Though the date he wrote his pamphlet is uncertain, his farm was active from the late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Instead of relying on buxom women and illustrations of red apples, Teator’s only image is a blue ribbon that borders the upper left hand corner of his brochure.

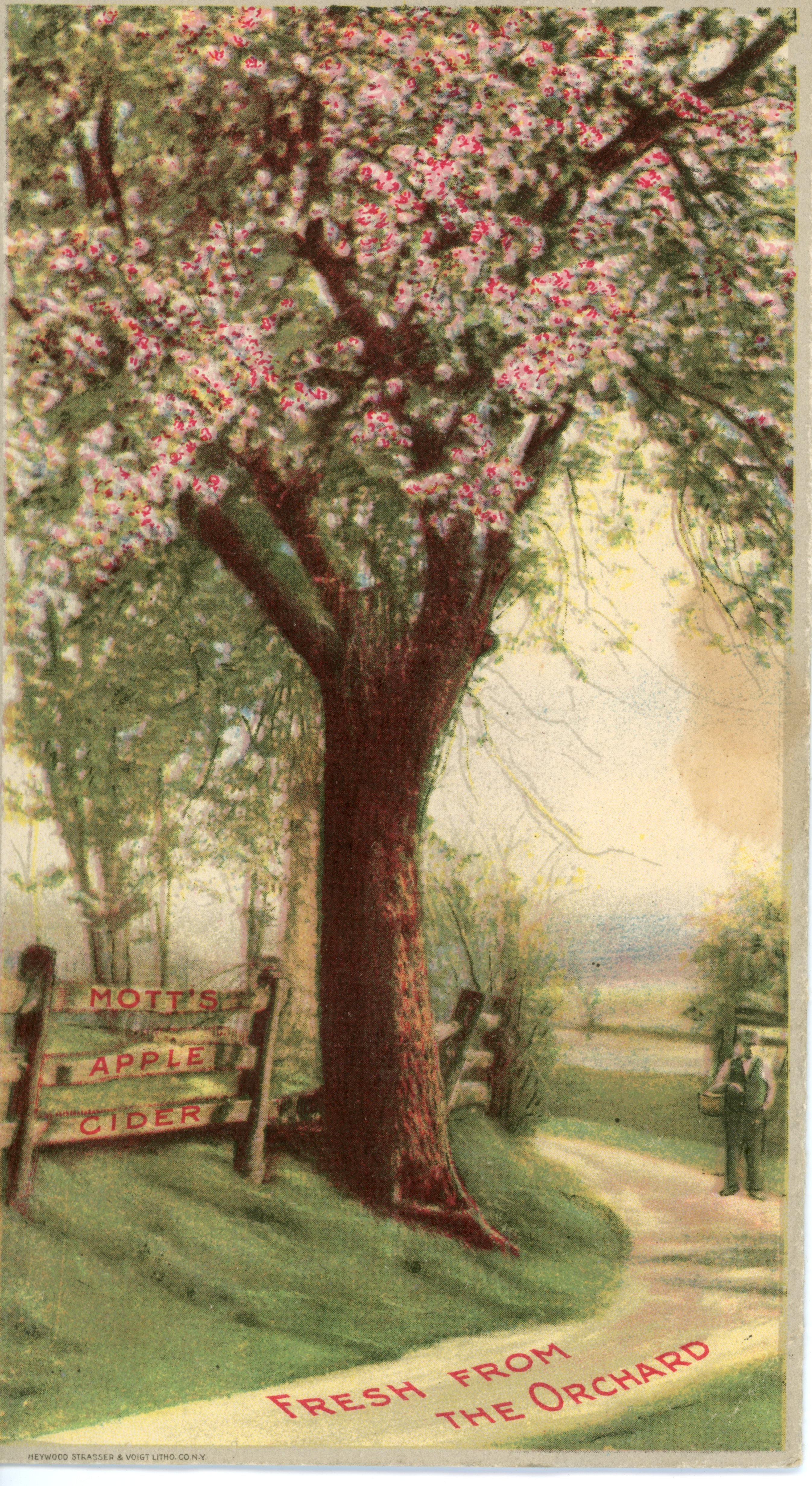

In this regard, the emphasis is not on glorified depictions of apples, as with the Mott’s Sweet Apple Cider pamphlet (which was present in Teator’s collection). The Mott’s circular, in full color with lush images of apple blossoms, the fruit itself, and amber cider, is much more visually stimulating than Teator’s brochure. Additionally, Mott’s assertion, “A glass of Mott’s Sweet Apple Cider a day Will keep the doctor away” is a claim likely unsubstantiated. At the time when Teator farmed, American advertisement was responding to consumer dissatisfaction with longtime practices of false advertisement. Samuel Hopkins Adams’ “The Great American Fraud,” which was a series of articles published in Collier’s Weekly in 1905, criticized this type of rhetoric, especially in relation to patent medicines. He wrote,

Gullible America will spend this year some seventy-five millions of dollars in the purchase of patent medicines. In consideration of this sum it will swallow huge quantities of alcohol, an appalling amount of opiates and narcotics, a wide assortment of varied drugs ranging from powerful and dangerous heart depressants to insidious liver stimulants; and, far in excess of all other ingredients, undiluted fraud. For fraud, exploited by the skillfulest of advertising bunco men, is the basis of the trade (Samuel Hopkins Adams, 1905:14).

Although stakes are low in ingesting Mott’s non-alcoholic cider with hopes of avoiding one’s doctor, the presence of such statements involves some deception of the customer.

By contrast, Teator’s brochure relies more on hard facts in persuading the customer to purchase his apples. He utilizes testimonials, including a quote from one man who said, “I have been in nearly every orchard in America that is worth while, but what I see here outshines them all.” Though the quote is somewhat vague in its implications, Teator made sure to explain what made his apples so superb. Not only are his farming techniques apparently superior, the selection and distribution of the apples also ensures that the product is excellent when it reaches the customer’s mouth. He asserts that “We sell you apples sound to the core, free from spots, worm holes, skin blemishes and defects generally” and tells customers that he will ship them in such a way that would avoid any defects along the way—by shipping the apples in barrels, not boxes.

The second point Teator makes in his pamphlet is key: “We are not offering low grade apples. No package received our BLUE RIBBON label unless it is of the highest standard.” As he asserts this, he gives his blue ribbon icon definite meaning. It is not merely a logo, it is a symbol of high quality.

However, as much as Teator explains the steps he takes to make his apples excellent, there is another quality in his brochure that persuades. He writes, “We take pride in pleasing the friends who buy our apples and wish to thank them for the many letters of appreciation we have received singing the praises of BLUE RIBBON APPLES.” By calling his customers “friends” and thanking them, what may have made his business excel was his reputation for kindness. His amiability becomes apparent in the letters he exchanged with both customers and friends alike; likely, his customers thought highly not only of Teator’s apples, but also Teator himself.

Works consulted: